《잃어버린 줄 알았어!》는 “우리가 꿈꾸는 탄력적인 사회공동체를 만들기 위해 예술과 건축은 어떤 사회적 합의에 기여할 수 있는가”를 조명해 보는 포럼이자 전시이다. 아울러 예술의 공동체 정신과 사회적

포용성 등 예술과 사회의 관계항들을 다시 생각해 보는 아이디어의 플랫폼이다.

이 프로젝트가 “포럼으로서의

전시”, “전시로서의 포럼”을 지향하는 것은 오랫동안 현대미술과

건축이 추구해 왔던 특정한 개념이나 형식, 스타일 중심의 엘리트적 실천으로부터 한발 물러나, 인류가 풀어야 할 다양한 형태의 ‘물려받은 상처’(inherited wound)들을 비롯하여 정치적, 사회적, 생태학적 숙명들을 회고하고, 다른 한편으로는 이를 더 기억하기 위함이다.

이 프로젝트가 제안하는 예술의 공동체 정신이란 예술과 사회의 관계론적

함의(relational implications)를 말한다. 즉

예술이 개인이나 공동체의 역사와 기억, 사회적 시스템 사이에서 어떤 연대 의식을 형성하고 사회적 합의에

참여하는지에 대해 토론한다. 앞에 언급한 ‘물려받은 상처’란 개인이나 공동체, 국가에 이르기까지 다양한 사회적, 역사적 매듭들을 포함하며, 부지불식간에 발생하는 수많은 우발적이거나

기획된 폭력으로부터 파생된 개인적, 공동체적 파괴의 사슬을 말한다.

예술은 국경이나 이질 문화를 초월하여 인간에 대한 존엄성을 우선적으로

선언하고 주장하는 표현공간이다. 아울러 배타성을 경계하는 자유와 상상력의 산물이다. 우리의 생생한 경험과 절망, 기억을 개별적, 집단적으로 묶어내고, 개인과 집단을 소통하게 하는 예술과 건축의

가능성은 그것의 메타 사회적 기능에서 나온다.

과거 모더니즘이 주창했던 선명성과 파편화는 과거와 미래, 남과 북, 진보와 퇴보, 급진과

보수를 가르고 결별시키는 방법으로 사용되었다. 그러나 생태학적으로 고통스러운 변화들이 부지불식간에 일어나는

오늘날의 현실을 고려할 때, 그러한 파편화된 담론의 항해 기술은 유효한 방향을 제시하지 못한다. 따라서 이 포럼은 급했던 걸음을 멈추고 우리들의 판단력이 호소하는 감지 장치들을 다시 점검해 보기 위한 협의체

역할을 하고자 한다.

이번 프로젝트의 초대 예술가는 중국의 딩 이(丁乙), 일본의 시오타 치하루(塩田千春), 한국의 엄정순(嚴貞淳)이다. 이 예술가들의 공통점은 인간이 숙명적으로 안고 살아가는, 매우 암시적이지만

도피할 수 없는 자아정체성에 대한 도전과 실천을 주제로 한다. 그리고 예술이 사회적 변화와 포용성에

대하여 어떻게 수용, 중재, 대응해야 하는가에 대하여 발언한다. 특히 동기가 분명한 민주화된 오늘날의 관객들이 어떻게 예술, 도시, 건축을 재발견해야 하는가를 안내하는 맥락들을 짚어본다. 참가 예술가들은

또 급속한 기술 발전을 바탕으로 과속 성장한 사회적 시스템이 초래한 인간의 부재와 생태적 위기를 진단하고 검증한다. 특히 우리가 학습하지 않는 이데올로기와 학습되지 않는 기억에 대하여 자기성찰의 목표를 찾는다는 점에서 중요한

맥락을 찾을 수 있을 것이다.

동아시아 지역의 한국, 중국, 일본 등 3개국의 예술가들은 오랫동안 서로 이웃하면서 상대방에 대한

다양한 관점을 제안하고 상호 진단하며, 예술을 통해 자신의 정치, 사회, 문화적이고 생태학적인 언어들을 개발하고 실천해 왔다. 프로젝트에

참가한 예술가들은 사회적 소수나 약자의 위치에 있는 개인을 비롯하여 사회적 공동체의 역사를 지탱하는 시대정신이나 기억을 시각문화적 문맥으로 실천해

오고 있다. 이는 특정 국가나 지역의 협소한 지정학적 이슈나 관계항들을 언급하는 것이 아니라, 예술의 존재론적 본질에 대해 답하고 또 제안해 온 예술가들이라는 사실이다. 아울러

이 같은 주제들을 연구해 오거나 관심을 가진 비평가와 큐레이터, 건축가, 학자, 도시계획자 등을 ‘연구자(researcher)’로 초빙하여 포럼을 진행한다. 포럼에서 발표하고

제안한 내용들은 전시 기간 중 단행본의 책으로 발간할 예정이다.

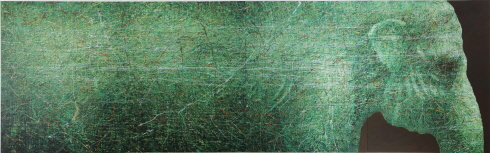

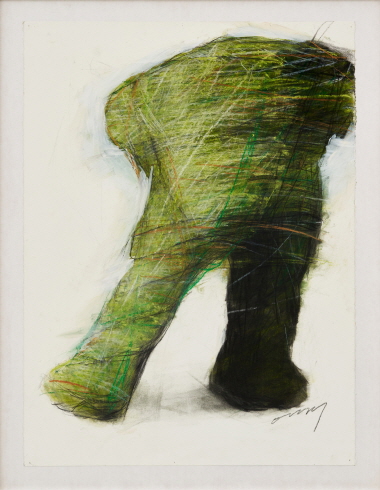

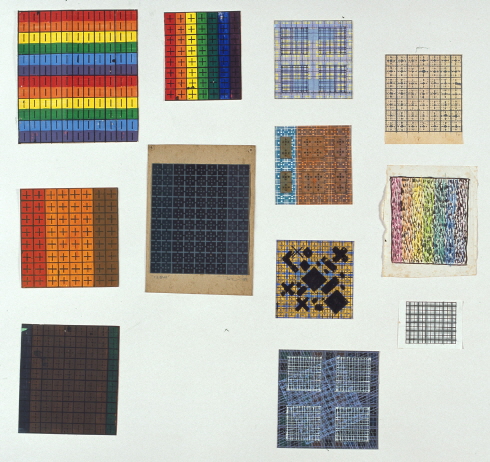

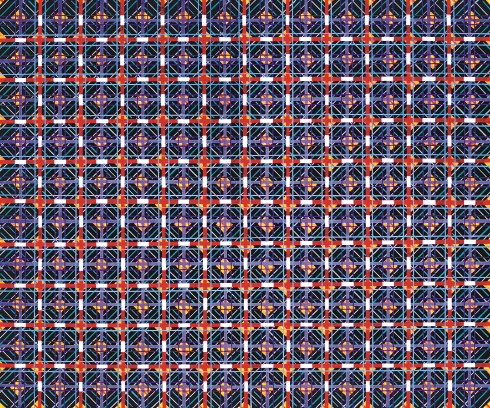

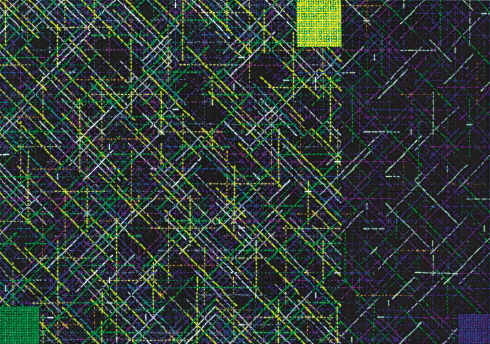

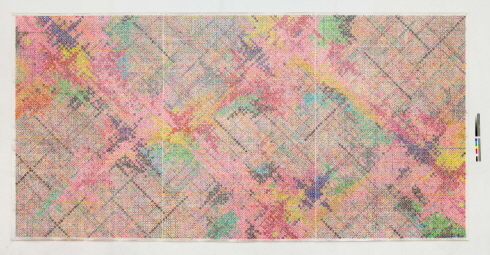

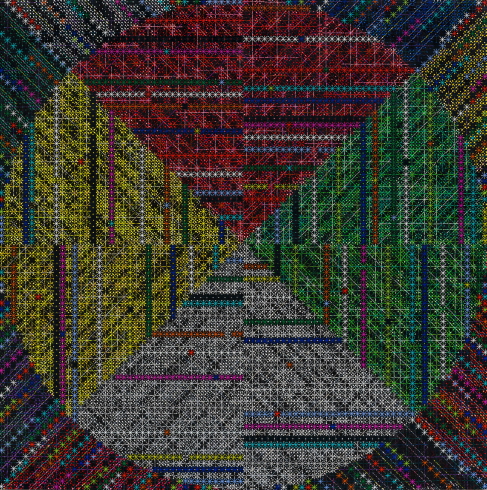

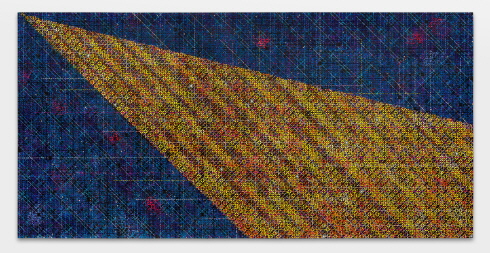

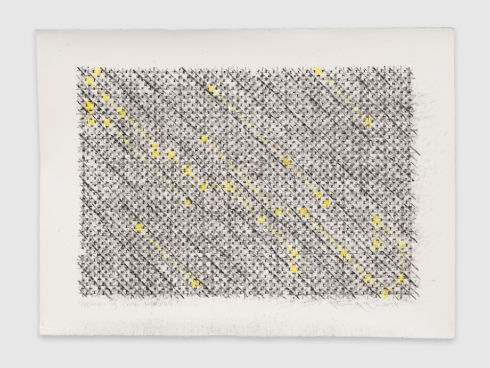

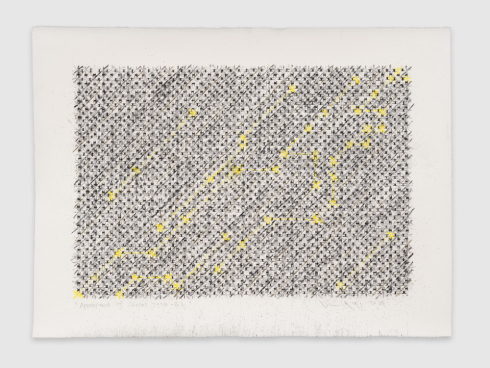

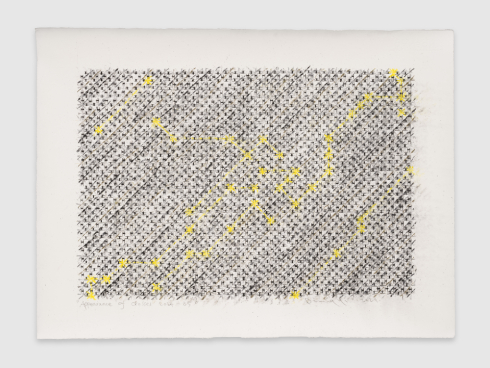

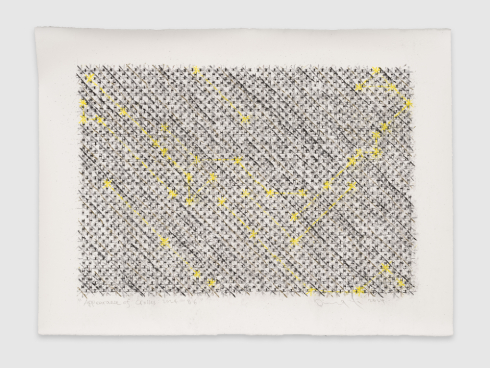

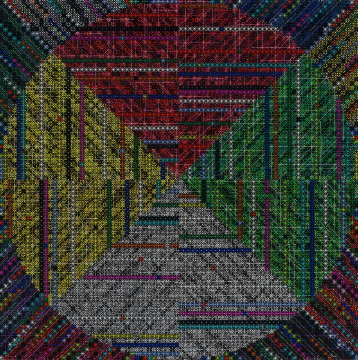

중국 예술가 딩 이는 1986년부터 40년 가까이 수학적 기호를 연상케 하는 십자(+)와 격자(x)를 표현 매체로 설정하여 1980년대 이후 중국 현대미술사에서

기하학적 추상의 선구자가 되었다. 그는 문화혁명 이후 1980년대부터

급속하게 등장한 아방가르드 운동의 실천적 1세대에 해당한다. 당시

신세대 현대미술가들은 문호 개방과 더불어 서구 현대미술의 영향을 강하게 받거나, 반대로 중국의 문화적

전통을 다시 들여다보고 중국성을 재발견하는 데 집중했다. 이와는 반대로 딩 이는 서구 영향도, 중국성에도 거리를 둔 채 예술 자체가 호소하거나 진단하는 본질적 문제를 질문하면서 자신만의 답을 찾아가고 있었다. 당시 젊은 예술가들은 새로운 것 자체를 가치로 보았으며, “더 과격하게, 더 실험적으로”를 외치던 시절이었다.

그는 다수의 젊은 예술가들이 더 크고 의미 있는 것들을 찾아 나설

때 오히려 의미 없고 하찮은, 아무도 관심을 두지 않는 수학기호와 같은 “+”, “x”를 일종의 표현과 전달 매체로 활용하여 추상 회화를 시작하였다.

모두가 거대한 ‘의미’를 찾던 시대에 ‘무의미’를 대안으로 제시하면서 역설적으로 거부 의사를 표현한 것이다. 그가 시작한 추상예술은 문화혁명기에는 자본주의의 퇴폐예술로 간주하여 금지되었던 장르이다. 그러나 그는 추상의 메타포가 내포하는 메시지들을 시대를 읽고 증언하며, 포용하는

표현적 대안으로 설정하였다. 그의 예술은 중국의 개혁개방에 따른 사회적 변화, 경제 발전, 대도시화의 모습들을 다양한제와 구성, 색상을 활용하여 기억하고 저장하는 메신저 역할을 했다.

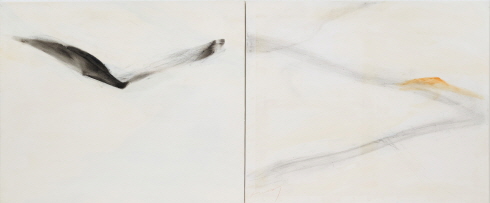

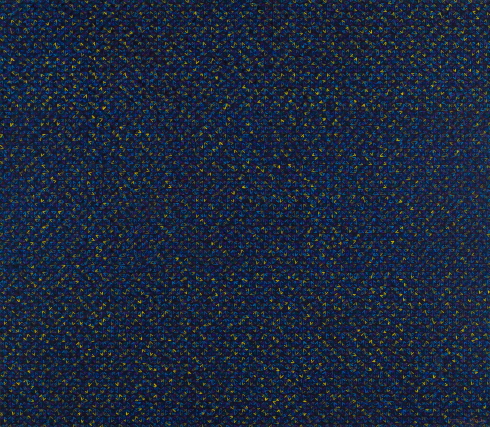

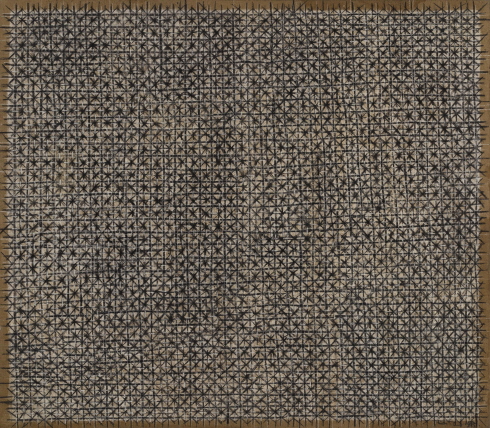

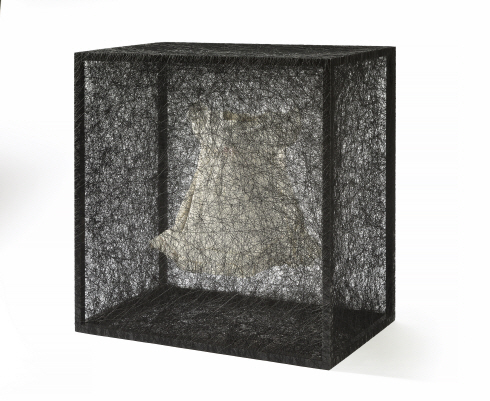

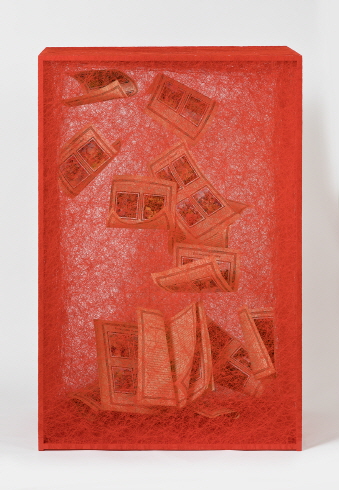

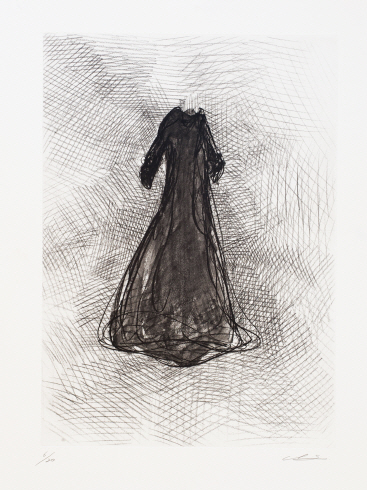

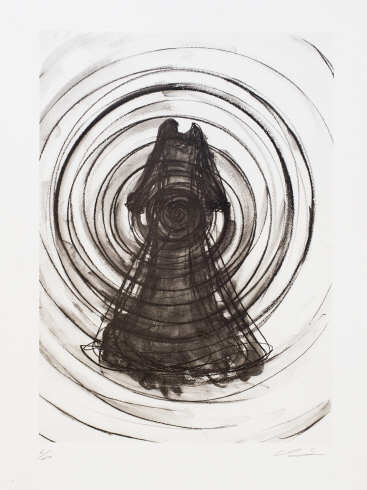

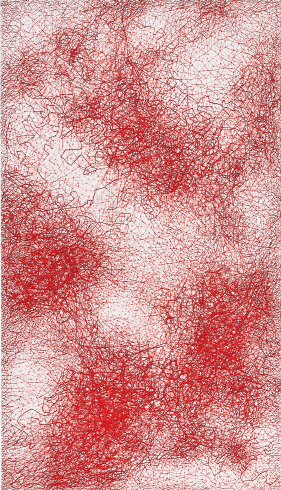

시오타 치하루는 1996년부터

베를린에 거주하고 있으며, 퍼포먼스와 실을 사용하는 설치미술가로 잘 알려져 있다. 그녀가 집중적으로 탐구하고 표현하는 메시지들은 특정 공간과 그 공간을 차지하는 물질과의 상호 연관성을 연구한다. 특히 우리의 일상을 지배하는 절실한 기억이나 신체, 경계영역, 소외 등 매우 개별적이면서도 사회적 상관관계를 질문하는 맥락들을 섬세하게 노출하고 해석한다.

붉은색, 검은색, 흰색 등의 실이나 호스를 활용하는 그녀의 설치작품은 작품이 놓이는 공간(방)에 대한 설정이 매우 중요하다. 실을 활용한 그녀의 설치작품에 자주

등장하는 소품들은 열쇠, 창틀, 헌 옷, 신발, 보트, 여행 가방, 플라스틱 튜브와 같은 일상적이면서 예술가의 개별적, 또는 집단적

기억과 연결된 구체적 물건들이다. 작품에 등장하는 색상과 소재는 중요한 암시적 요소이며, 이러한 소품들 가운데는 생명을 상징하는 붉은 피 색깔의 실이나 소품들이 다양하게 얽혀 있다. 이러한 구성과 전시에 사용되는 작은 소품들은 삶의 주변이나 우리들의 DNA에

살아서 꿈틀거리는 기억들을 연상하도록 한다.

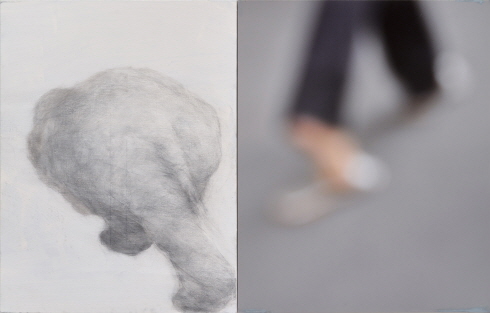

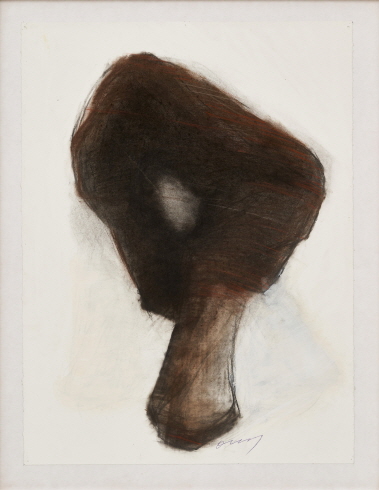

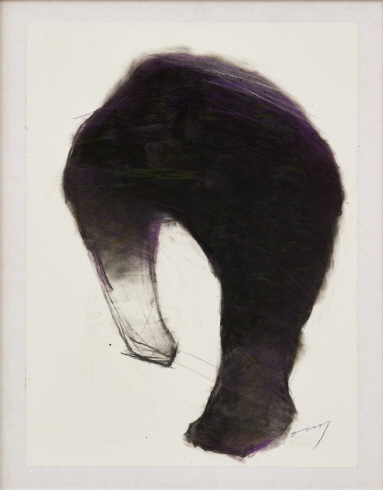

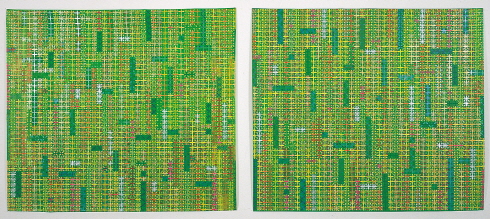

전시장에서 절대로 금지된 터부는 천재적 예술가들의 손을 거쳐 제작된

숭고한 미학적 세례품인 예술 작품을 관객들이 만지는 것이다. 그러나 예술가 엄정순은 역으로 관객들에게

작품을 만질 수 있도록 권유하면서 작가가 설정한 주제로 참여를 유도한다. 가령 시각장애인들에게 코끼리를

만지는 것은 코끼리를 보는 것이다. 불교 경전인 『열반경』에 “장님

코끼리 만지기”라는 말이 있다. 코끼리는 손의 감각으로 파악할

수 있는 작은 물체가 아닌 거대한 볼륨을 가진 짐작 불가능한 물체이다. 전체를 만질 수 없는 거대한

물체는 만지는 부위의 특성만 손으로 볼 수 있다. 본다는 것과 보지 못하는 것 사이의 차이는 하늘과

땅만큼 크다. 예술이 소수자들을 돕고 치유할 수 있는 사회적 포용성은 절대적이며, 그 사회적 합의를 도출하는 과정 또한 예술의 사회적 동의나 참여와 관계가 있다. 보는 것과 보지 못하는 것 사이의 사회적 격리는 거대한 것이며, 소수자를

돕는 제도적 장치가 없으면 불가능하다.

예술가 엄정순이 자주 언급하는 사회적 포용성이란 관용이나 양보와

같은 겸양의 미덕을 말하는 것이 아니라 소수의 약자와 그들의 삶(생명)과

연결된 제도적 장치와 참여의 문제이다. 그가 사회적으로 소외받는 소수자들의 세계를 위해 행하는 예술적

실천이나 전문적 연구는 가상이나 상상이 아니라 현실 그 자체이다. 시각장애인들이 이해하는 코끼리의 코와

귀는 비장애인이 생각하는 동물 코끼리가 아니라 거대한 물체에 대한 상상력을 동원하여 축소되거나 확장된, 비현실적이거나

추상적인 대상이다. “또 다른 보는 방법(Another Way of

Seeing)”으로 명명된 엄정순의 프로젝트는 오차가 배제된 현실인 동시에 상상력이 동원된 예술이자 사회적 수단이 된다.

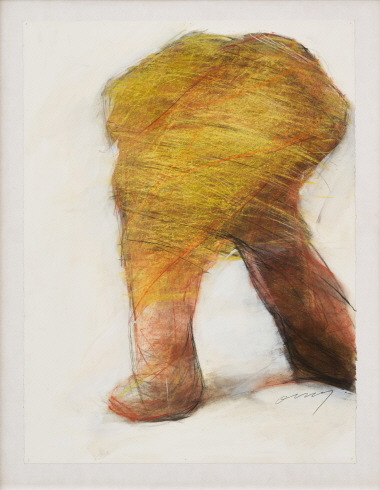

6백 년 전

한반도에 처음 들어온 코끼리를 처음 본 정부 관리가 그것의 괴기한 외모를 조롱하고 학대하다가 코에 맞아 죽는 일이 발생하자 그 코끼리는 남쪽에

있는 외딴섬으로 유배되었다. 이를 보고받은 세종대왕은 “물과

풀이 좋은 곳으로 보내어 병들고 굶어 죽지 않게 하여라”는 교지를 내렸으며 이 사실이 세종실록에 기록되어

있다. 코끼리에게 코는 권력이자 위계이지만 그것을 한 번도 본 적이 없는 비예술가들, 사회적 약자들이 만들어내는 예술은 중요한 사회공동체적 참여와 포용의 예술이 된다. 권력의 상징인 코를 본 적이 없거나 잘 모르는 사회적 약자들이 코가 없는 코끼리를 만드는 아이러니는 권력이나

위계와는 관계없는 우화가 된다.

참여 작가들의 작품은 시간과 역사,

개인과 집단의 기억, 진화와 발전, 포용성과

배타성 등 사회인류학적 메시지의 상호작용을 포착한다. 그들의 메시지는 예술이 건물, 도시, 기술 발전, 환경

등의 학습된 문제에 대한 대안을 제공하면서 사회적 의미를 전달하고 개입하는 데 중요한 역할을 한다는 사실을 상기시킨다. 참여 작가들은 20세기 후반부터 서구보다 빠르게 진행된 동아시아의

급속한 도시화로 인해 ‘함께 살아감’의 정신을 상실한 둔한

도시문명을 상기시킨다. 그리고 도시인의 소소하고 아름다운 추억을 앗아가는 대도시화와 그 소비주의의 그림자를

기억하게 한다.