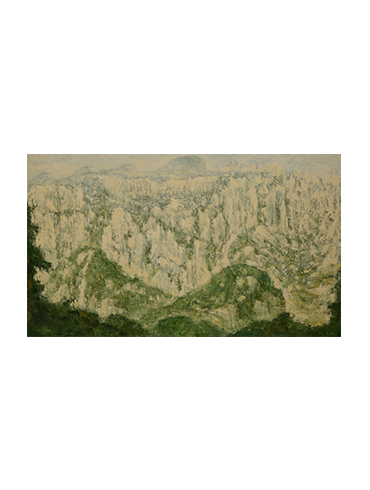

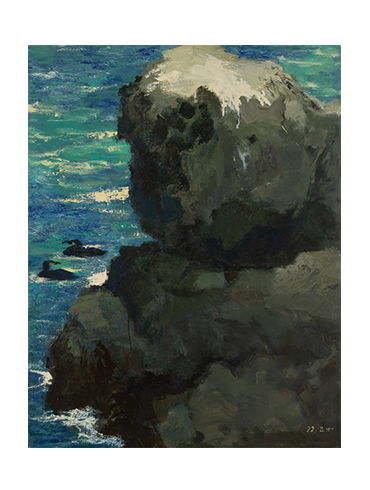

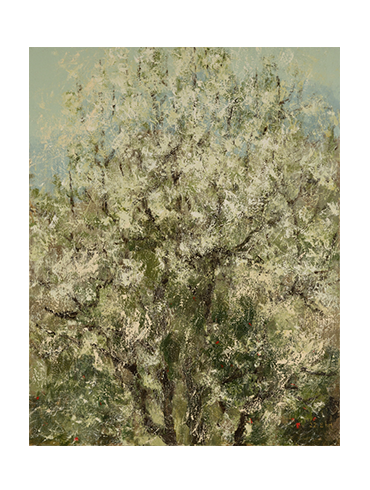

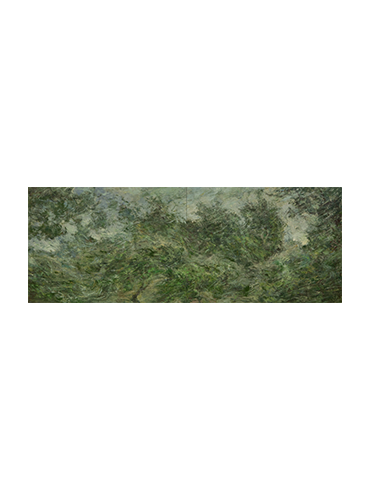

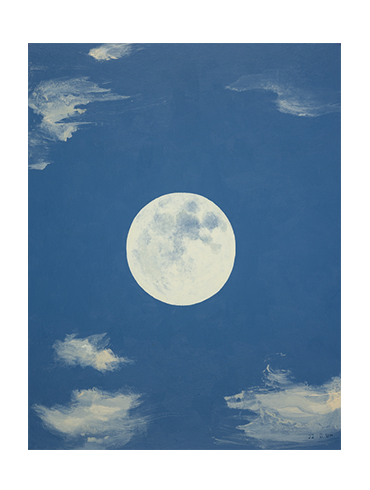

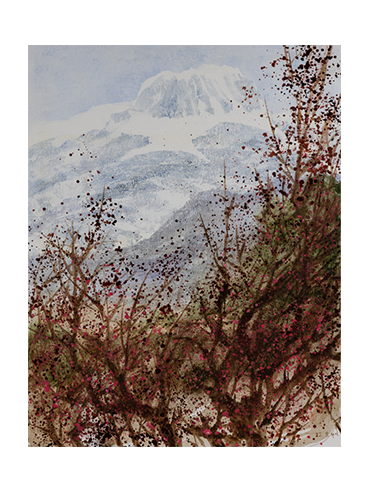

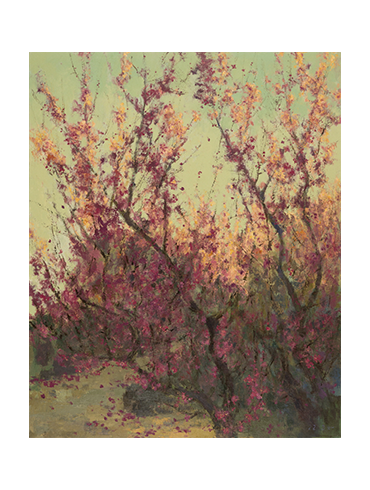

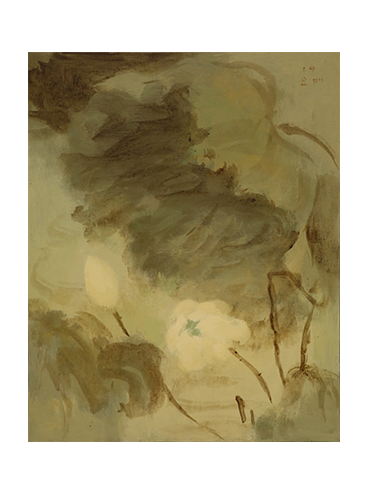

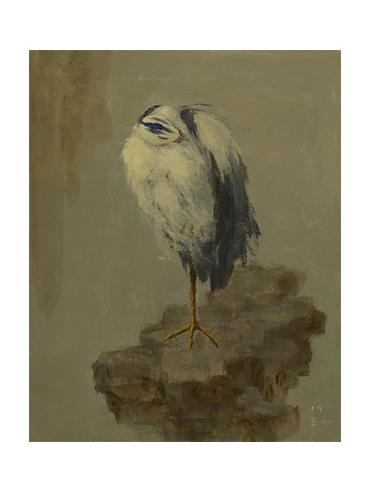

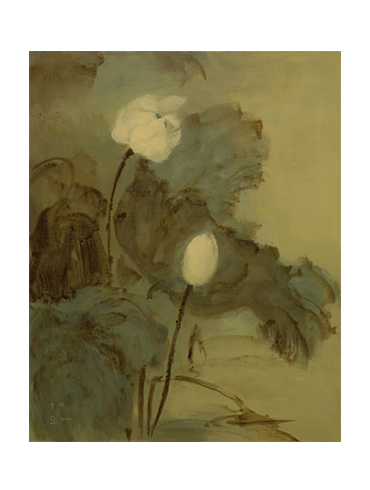

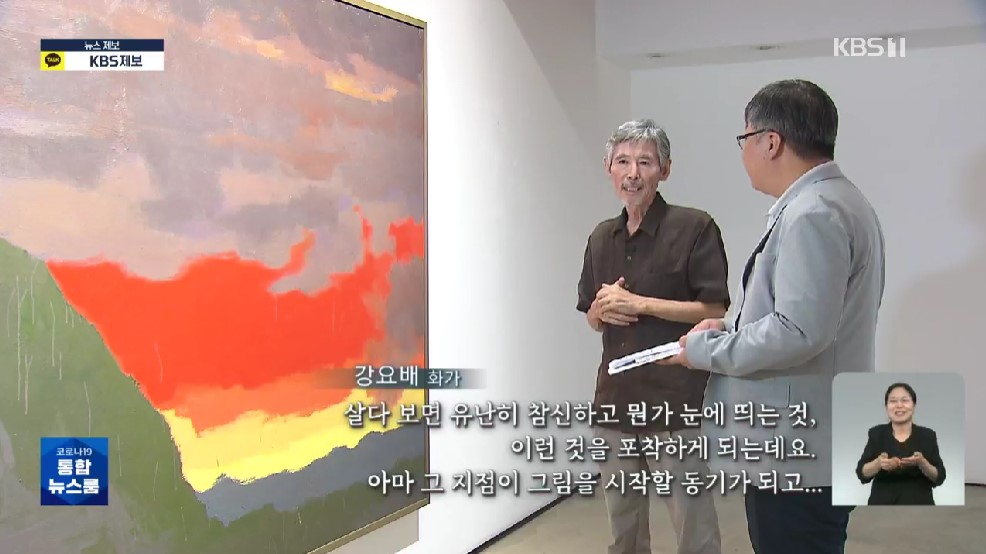

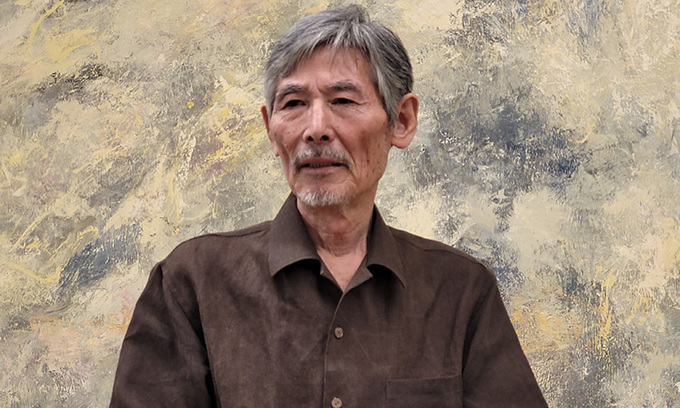

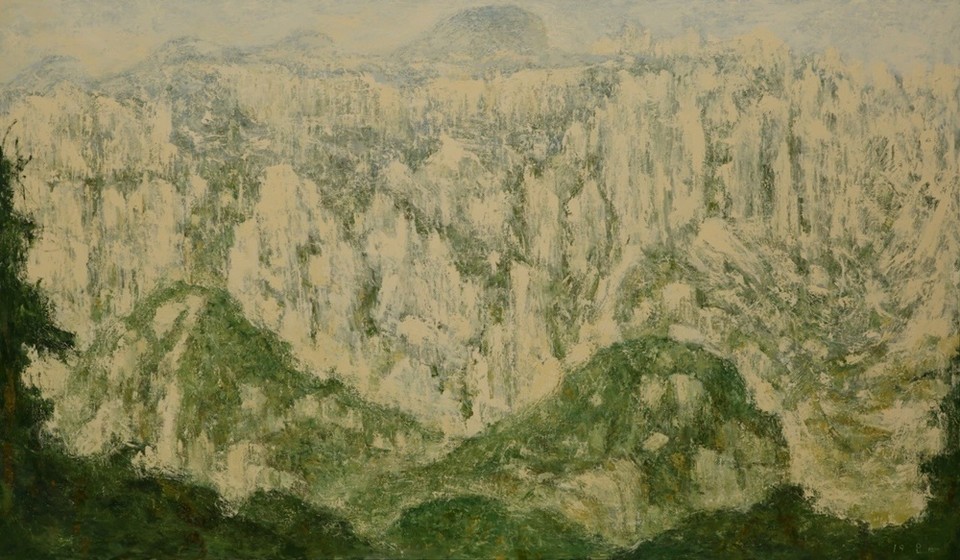

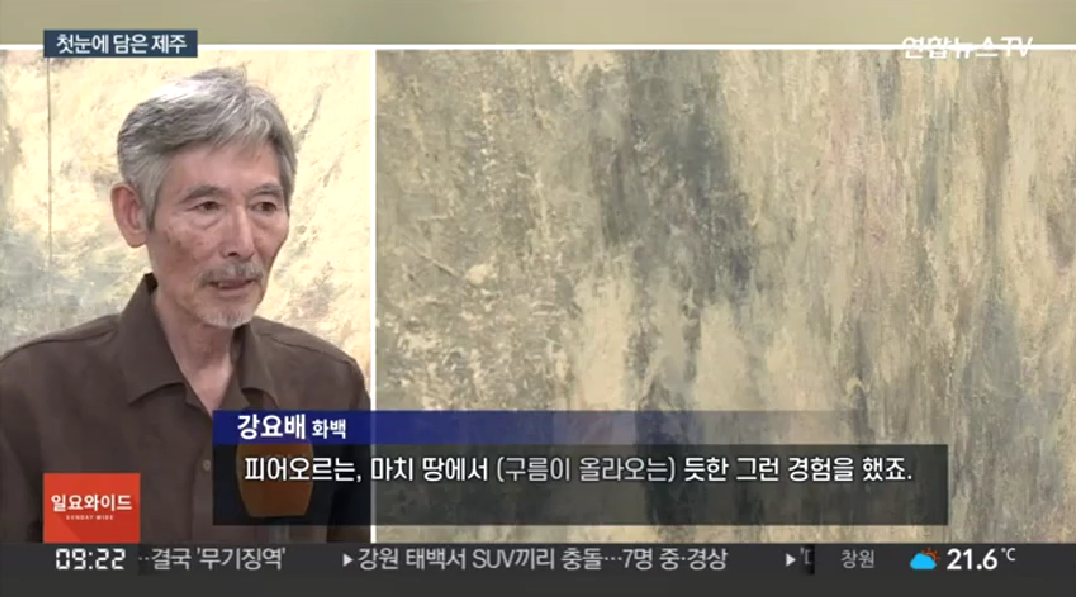

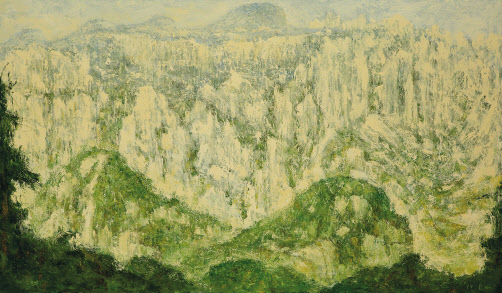

강요배가 그리는 산과 풍경은 스스로 그러하다는 뜻의 자연(自然)이다. 사람이 자연으로부터 분리되면 자연의 바깥에 존재하게 된다[ex-sist]. 자연의 바깥에 존재하는 것은 인위이며 문화이다. 서구의 풍경화는 대상을 객관화한다. 화가는 대상(자연)으로부터 분리된다. 이에 반해 강요배 작가는 대상과 분리되지 않고 하나가 된다. “자연을 만지고, 자연 속에 살아봐야” 그릴 수 있는 의경으로서의 그림이다. 그 의경의 발원지는 올곧은 역사인식과 무한한 국토애(國土愛)이다. 자연(공간)과 역사(시간), 그리고 자아(주체)가 총체적으로 통합된 경계에서 획과 속도, 벡터와 강약이 더불어 용솟음친다. 거듭 말하자면 작가는 “단순한 객체로서의 대상이 아니라 주체의 심적 변화를 읽는 또 다른 주체로 다룬다.”

「원인(原人)과

원도(原道): 사람을 묻고 도리를 묻다.」 中 발췌 | 이진명(미술비평·미학·동양학)

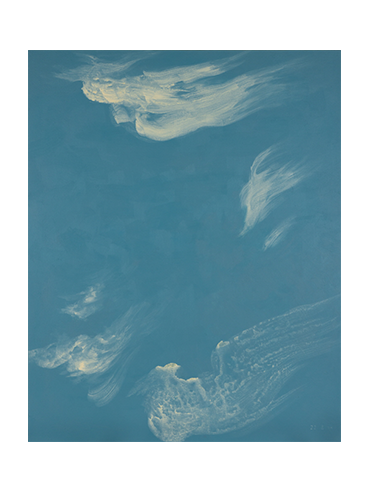

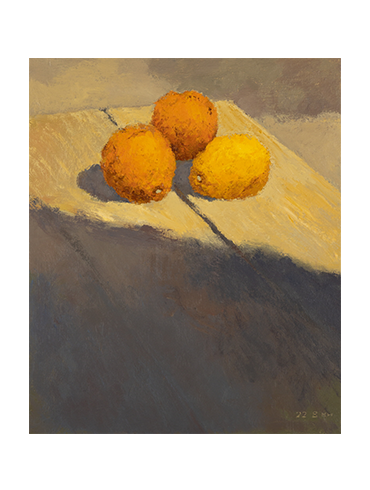

우주적인 기류의

변화를 색면의 변화, 색감의 차이로 치환하여 색채 운동감을 부각시킨 색면추상은 강요배의 회화세계를 민중미술의

서정적 정서나 제주 지역미술의 풍토성을 반영하는 대표 화가의 타이틀에 포획시켜온 관성적 평가에서 나아가, 통시적

현대미술의 또 다른 경향으로 바라보게 한다. 강요배의 회화적 실험은 나선형적 사유 회로에 따라 유동적으로

움직이며, 동양화와 서양화의 장르적 분류를 벗어나 미술에서 ‘그리기’라는 가장 오래된 고대적이고 원시적인

표현방식의 형식적 실험이 2020년대에도 여전히 유효하다는 현재적 응답으로 보인다.

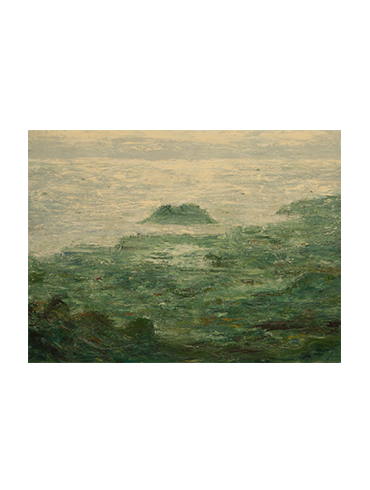

첫눈에, 첫 마음에 무엇이 낚일 것인가? 바람이 내는 소리를 듣는다.

「천기(天機)의

관조, 나선형적 사유」 中 발췌 | 김정복(미술사 연구자)